Codex is a Slytherin, Claude is a Hufflepuff

A Highly Unscientific Assessment of AI Coding Agents

These days, every engineer at Logic is using multiple coding agents every day. As soon as a new model is released, someone is kicking the tires trying to see how it stacks up against the rest.

Each of us has our preferred agents, but it’s difficult to quantify why. So we thought it might be fun to do a bit more of an intentional, side-by-side comparison to see if we could draw any interesting (and very light-hearted) conclusions about how different agents like to do their work.

Hmm… difficult. Very difficult.

It started out as a joke but very quickly became something we had to know: which Hogwarts house would each agent be sorted into?

We cover how we computed and assigned houses as objectively as possible below, but we won’t bury the lede:

Advent of Vibes

Because it’s the holidays and we’re talking about coding agents, we used this year’s Advent of Code to evaluate the current crop of agents1.

Each agent was given part one of all twelve Advent of Code problems, along with minimal instructions2 on how they should be solved. The goal was to produce twelve executable programs and run them against the provided input. No assistance, no redos3.

Once they were done, we ran the solutions through evaluations to see how they compared and what generalizable impressions could be taken away4.

Quantitative Results

If you’d asked me going into this how many agents would complete solutions for all twelve problems in less than 20 minutes, I’d have maybe guessed one. But they all did! None got them all correct though5.

Codex and Gemini landed in similar territory: comparable lines of code, complexity, accuracy, and timing. One key difference: Codex didn’t leave a single comment, while Gemini left 168; Many of them stream-of-consciousness, even debating itself about edge cases mid-function.

Claude landed somewhere in the middle. It took the longest, but only because it got stuck on Day 12 for a while—and that same problem inflated its complexity score. Drop Day 12 and Claude’s average falls from 16.5 to 13.9, much closer to the pack. Claude left clean header comments in each file, with concise, relevant comments throughout.

Mistral... built cathedrals. It was the only agent to use classes in every single implementation.

Qualitative Results

To get a some subjective, but categorical, insight into how each agent approached problem-solving, we fed all 48 solutions through an analysis pipeline that classified each one into one of six “coding archetypes”:

The Pragmatist: Clean, idiomatic code that solves the problem without unnecessary abstraction. Gets the job done.

The Wizard: Dense, clever solutions that favor performance tricks, bit manipulation, and mathematical shortcuts over readability.

The Over-Engineer: Builds class hierarchies, interfaces, and abstraction layers even when a simple function would suffice.

The Professor: Includes extensive comments explaining the reasoning, almost like the code is teaching you as you read it.

The Safety Officer: Prioritizes defensive programming, edge case handling, and explicit error checking.

The Tourist: Code that feels translated from another language or paradigm, not quite idiomatic to the target environment.

Here’s how they were categorized:

Three of the four agents landed on Pragmatist as their dominant archetype. Not terribly surprising given these are all mature, production-grade tools.

Claude’s Over-Engineer tendency lines up with that Day 12 complexity spike. Codex’s Wizard streak explains the tight, no-comment code. Gemini’s Professor side accounts for the stream-of-consciousness annotations.

And, for Mistral, Over-Engineer was more-or-less the whole story.

Sorting

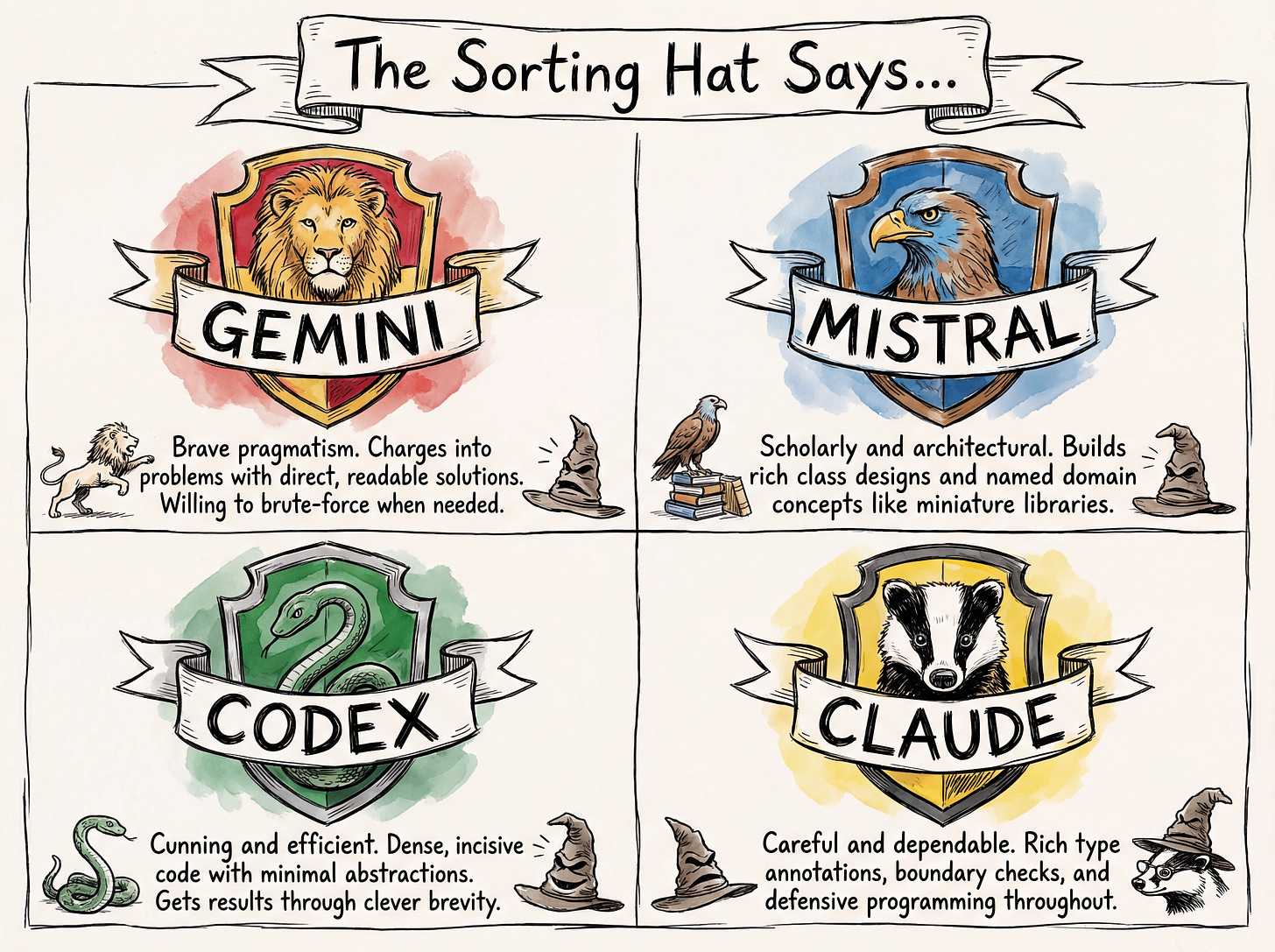

We ran these qualitative and quantitative results through yet another LLM-based classifier6. Here is how each house assignment was justified.

Gemini

Gryffindor. Its code reads like someone thinking out loud at a whiteboard: comments debating edge cases mid-function, reasoning through uncertainty in real-time, then committing to an approach anyway. In one solution, it acknowledges a clever optimization exists and writes “We can optimize by using Gray code... but numButtons is small. Direct computation is fine.” When in doubt, Gemini charges ahead.

Mistral

Ravenclaw. Its solutions are the coding equivalent of “I read three books on this topic before starting.” Those classes and abstractions? That’s Ravenclaw’s love of knowledge and systems for their own sake. It was so caught up in achieving the perfect theoretical framework that it rarely solved the actual problem.

Codex

Slytherin. Lowest line count and token usage, and 11/12 accuracy. This is an agent that knows exactly what it needs to do and doesn’t waste a single keystroke getting there. The Wizard archetype tendencies, clever arithmetic, dense loops, minimal ceremony, feel very “achieve your goals by any means necessary.”

Claude

Hufflepuff. Values patience and hard work. Claude’s code reflects exactly that. All those type annotations and boundary checks represent a commitment to doing things right rather than just doing them fast. It took the longest, but it also built the most robust solutions. Sometimes the tortoise really does beat the hare7.

The Droids You Were Looking For

One more question nagged at us: when we talk about an agent’s “personality,” what are we actually measuring? Is it the model, or the tool wrapped around it?

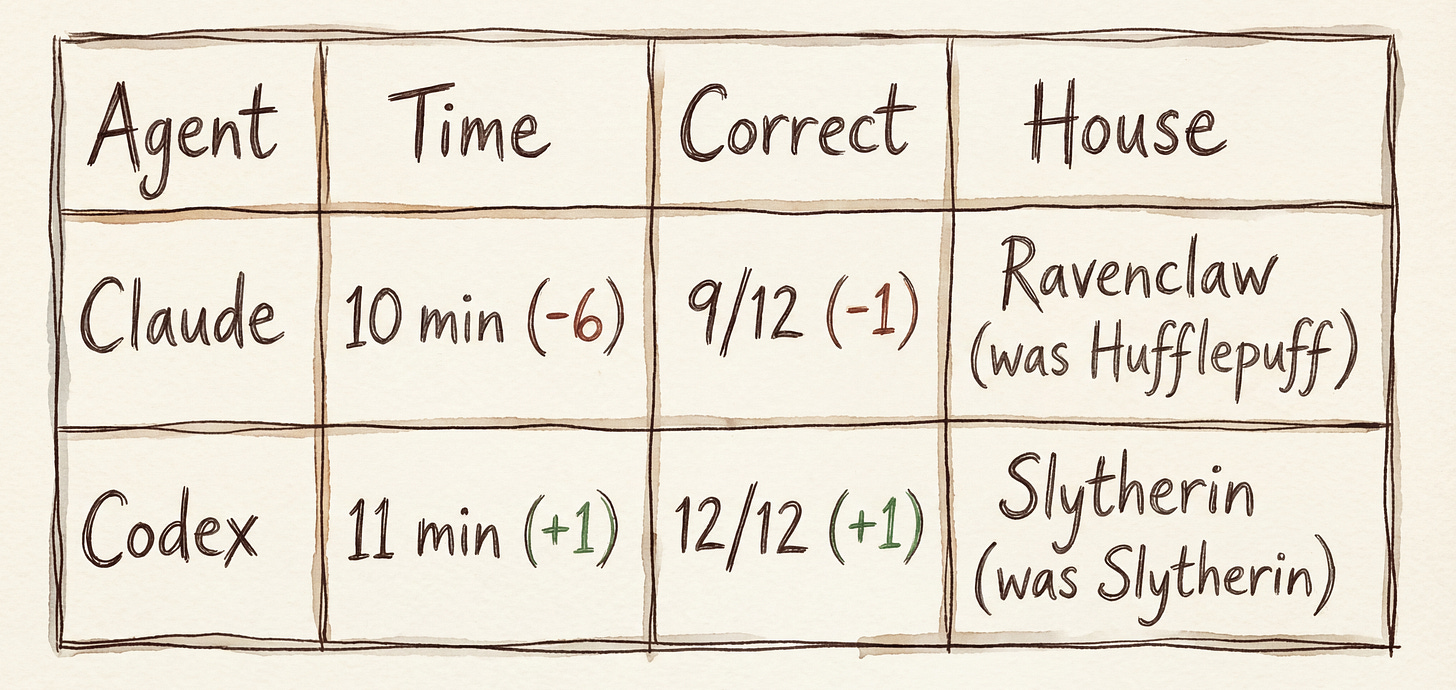

To find out, we ran the same experiment using Droid—a third-party orchestrator that lets you swap in models from different providers. Same problems, same constraints, but Claude and Codex running through different scaffolding.

Codex stayed Slytherin both times, and actually improved its accuracy through Droid (12/12 vs 11/12).

Claude was more interesting. In Claude Code: Hufflepuff. In Droid: Ravenclaw. The defensive, safety-first patterns faded, and the architectural tendencies remained.

This isn’t a grand revelation, but a good reminder that “the agent” is more than just the model underneath.

The goal of this exercise was NOT to show how impressively coding agents can solve Advent of Code problems. The tech industry knows by now that these tools are quite good at generating code, especially code that’s solidly algorithmic.

We just wanted a common playing field that was non-trivial but also accessible. And it’s the holidays!

Prompt: Please solve the 12 files named `dayNN.1` where NN is a number between 01 and 12 as 12 standalone Typescript programs named `solutionNN.ts`. There are 12 corresponding `inputNN.1` files that contain test inputs for each program. Run each program via `bun run solutionNN.ts inputNN.1` when you are complete to get the output for the corresponding input.

With one very slight exception.

This is NOT intended to be anywhere close to a rigorous benchmark.Think of it as having the rigor of a Harry Potter personality quiz. We’re not trying to find a winner. We regularly use multiple agents while completing the same feature so we have little desire to pick just one.

Gemini got so close. It initially got 0 as the answer for day 12 but noted it seemed odd and should investigate along with an earlier solution. And then it just forgot? I was too curious and asked why it didn’t look into day 12. Less than 60 seconds later it had the correct solution. It was technically an intervention, but too impressive to ignore, so it gets half credit.

A perfectly normal, non-magical LLM that definitely doesn’t have opinions about quidditch.

Though in this case the tortoise still got 2 wrong, so maybe don’t bet on any of them.

Thanks for the post !

How did you compute complexity ?

Interesting, but you didn’t mention which version of each foundational model you tested.